Chapter 2: Economic self-sabotage

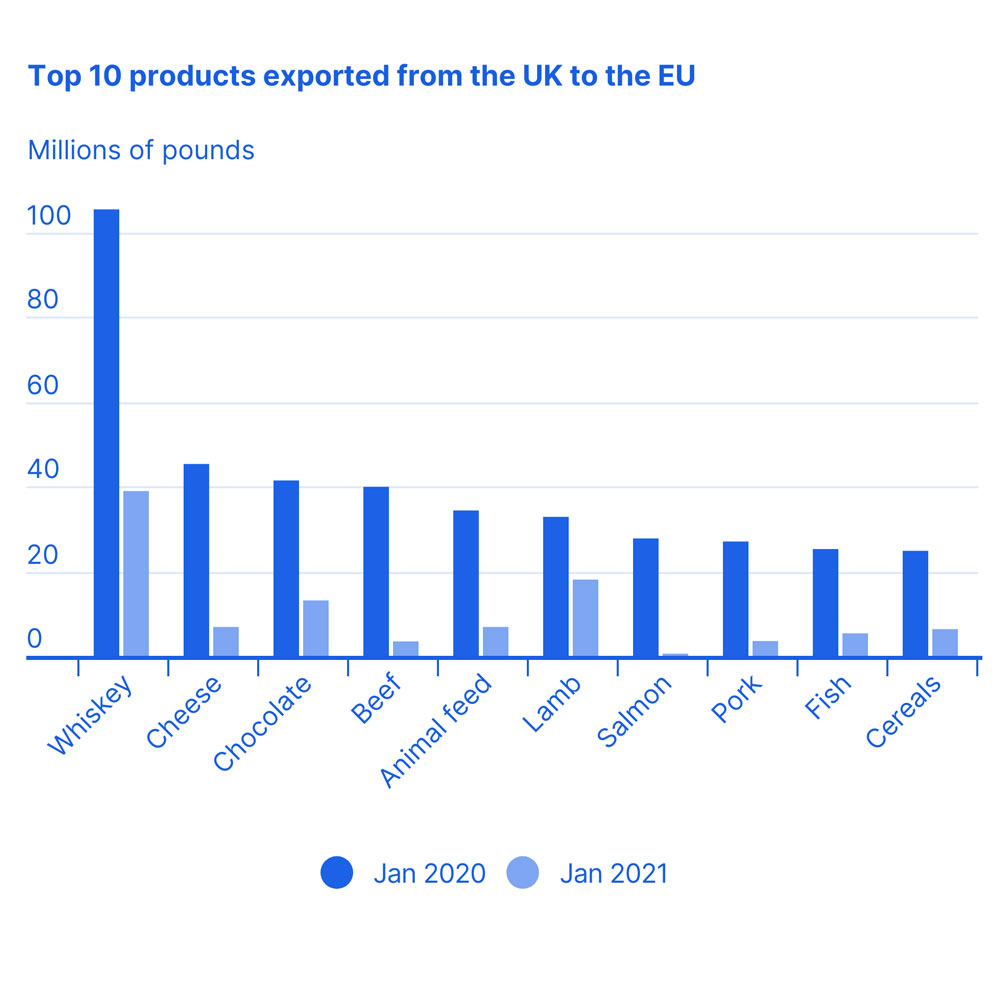

Brexit has so far seen some industries plunged into sudden and acute crisis – most noticeably fishing, shellfish and some other food exporters. The government’s promise of “no barriers to trade” did not last even one hour after the Brexit deal came into force.

British food and drink exports to the EU fell dramatically after the end of the transition period. Salmon exports crashed by an incredible 98%.

For some individual companies the difference has been night and day. Baron Shellfish, a 40 year old Yorkshire firm that exported £1 million of lobsters a year, mostly to Spain, was forced to shut down entirely because of Brexit. Bridlington, once called the “lobster capital of Europe”, had found its access to European markets effectively cut off by the Brexit deal. Sam Baron, the firm’s owner, said: “All we have had is bullshit from the government, promises that haven’t been kept. I am winding up the business while I still have enough to pay redundancy to my staff… It is all Brexit-related – the extra costs, extra paperwork.”

To take another example, UK firms can no longer sell small boxes of cheese to the EU at all because each one would need a veterinary health certificate that costs 7 times more than the cheese itself – and plans for larger wholesale shipments have also proven impractical. Simon Spurrell of the Cheshire Cheese Company told the Financial Times: “The government has successfully removed us from the EU as a business, it is no longer commercially viable and our distributors in France, Spain and Germany are not interested in doing business with us because of both the extra cost and the difficulties with the paperwork.”

The government offered no help, instead telling the cheese company that it should forget European sales and break into “emerging markets”. (It is unclear exactly where the government believes these untapped markets for cheese are emerging.)

In a second category we could place musicians and others who rely on travelling to work, who are beginning to warn that the loss of freedom of movement will make it impractical for them to earn a living (see chapter 5).

A punctured economy

The effects of Brexit on most of the economy, however, are ‘slow burn’ – and have been further obscured by the pandemic. Britain’s economy has a puncture: it does not necessarily feel like it is shrinking from moment to moment, but nevertheless the air is slowly leaking out. The UK’s trade with EU countries fell by 23% in the first quarter of Brexit.

While the occasional heavily-subsidised car factory or 50 jobs added in Heinz ketchup production gets the headlines in the Brexit-supporting press, the bigger economic story is small and medium-sized companies moving their headquarters into the EU. While large multinationals have not generally needed to do this (as they already have EU bases), for many smaller companies and particularly for export-based businesses, it has been the only decision they have been able to make in order to preserve the largest part of their trade.

Most businesses moving do not make a big song and dance about it, for fear of provoking a Brexiter backlash – but move they do. Medicines, textiles, sportswear… company after company has been forced to set up in the EU, sometimes at great speed. The Guardian reported the tale of Sussex pharmaceutical company Mediwin, which had to “bundle a production line into a white van and take it to Amsterdam” to ensure it could continue to sell its medicines in France.

In January 2021 even the UK government’s own Department for International Trade advised some UK businesses to register new companies in the EU.

Dutch warehouses have reported a ‘Brexit boom’. “A lot of companies are thinking of establishing themselves on the European mainland and the Netherlands is one of the big hubs for that,” says Michiel Bakhuizen of the Netherlands Foreign Investment Agency. “We are pretty busy because of Brexit at the moment.”

While some UK companies are setting up EU hubs or moving, most non-UK companies looking to sell to Europe are no longer even considering Britain as an EU base. Why would they? Britain is relatively expensive and now only gives easy access to a tiny market. This fall in investment coming into the UK did not wait for the end of the transition period and began declining in 2019 and 2020.

Where did all the workers go?

Meanwhile, back in Britain, labour shortages are starting to bite in sectors that relied on workers from the EU, particularly (at the moment) hospitality, construction, farming, food packing and transport. More than a million EU workers are estimated to have left the UK since late 2019.

A survey by the British Chambers of Commerce in July 2021 showed that 70% of companies that had tried to hire staff in the preceding three months had struggled to do so. A separate survey of more than 400 recruitment firms showed a sharp rise in hiring demand and an unprecedented fall in the availability of candidates.

Poultry production has fallen by 10% “because of the shortages of workers across farming and processing”. On farms, fruit and veg rot in the fields as farmers are unable to recruit enough pickers.

Before Brexit, more than 30% of hospitality workers in the UK came from the EU, rising to over half in London. Industry group UK Hospitality said in May 2021 that there was now a shortfall of about 188,000 workers, with “particularly acute” shortages of front-of-house staff and chefs.

Again, while some are trying to blame this exodus on Covid, industry voices are clear about the main factor. Restaurateur David Moore said Brexit was “definitely the biggest” factor behind staff shortages, as the “heartbeat” of the hospitality industry was “young kids” from the EU. Itsu boss Julian Metcalfe agreed, saying the food chain’s “young European chefs” have “now sadly all disappeared” – because “they are not allowed in”. Even Tim Martin, the Brexit‑backing boss of pub chain Wetherspoon’s, has bemoaned the staff shortages. Having caused the problem, he now wants new rules to… let the pub sector recruit workers from the EU.

Adequate food?

The shortage of an estimated 100,000 HGV lorry drivers is becoming acute as many European drivers have left the UK, and at the same time cross-border hauliers from across Europe are declining to come to Britain and go through the burden of extra paperwork and the risks of getting stuck on the wrong side of the Channel, as happened to many over Christmas 2020. The government built lorry parks expecting thousands to be stuck in customs checks for days or weeks, but the reality has been worse – most drivers simply refuse the work, even if offered multiples of the usual fee.

Will there be food shortages? That’s the question newspapers are asking. We are already (in summer 2021) starting to see scattered empty shelves. Industry leaders in June warned in a letter to the government of the risk of “critical supply chains failing at an unprecedented and unimaginable level”. As of this book’s second printing (Sept 2021), shortages are worsening and there are warnings about large-scale supply chain failure at the Christmas peak.

Apart from the possibility of an acute crisis to come, there is also the gradual realisation that shortages somewhere around the current level, and likely getting worse over time, are an inherent part of Brexit. “The UK shopper could have previously expected just about every product they want to be on shelf or in the restaurant all the time,” says Ian Wright from industry group the Food and Drink Federation. “That’s over and I don’t think it’s coming back.”

While that doesn’t mean empty supermarkets, it means a fall in food availability and choice to levels last seen in Britain in the 1970s, with a particular lack of the imported European foods that we have all become used to. It is often forgotten that the periodic food crises of the 1970s were one important reason why the UK wanted to join the EEC to begin with, and food was a major issue in the 1975 referendum debates. Voters were told to think of the Common Market as the ‘Common Supermarket’, with its ‘well‑stocked shelves’. Those who claim that Britain had no food problems before its EEC membership are deliberately misrepresenting this history.

Today, the press are diplomatically putting the lack of lorry drivers down to “Brexit and Covid”. But even though every country in Europe has Covid cases, it’s only Brexit Britain that is seeing labour shortages to this extent. The old Dominic Raab boast that there will be “adequate food” is looking doubtful.

So far the government’s only answer to the shortages has been to loosen the rules about lorry drivers’ hours, putting road safety at risk to try to pretend everything is fine, and perhaps they will find some other quick-fix to paper over the cracks before shortages reach a crisis point.

Even if the government continues to bluff, bluster or bend the rules at the last moment to ameliorate the most pressing problems, the cumulative economic damage from Brexit will be enormous – and while it is difficult to establish a direct cause-and-effect for much of this economic decline (see chapter 5), it is not possible for an economy to defy gravity for long: once the real-world effects will start to be felt in everyday life, the government’s popularity will surely be dented.

All of this will be exacerbated by the end of free movement from the EU. There has rightly been much attention on the Settled Status deadline, which has been an administrative nightmare for Europeans living in the UK and raises the frightening prospect of people who have not applied being criminalised in the future. What has been less acknowledged is the economic side of the loss of free movement: by blocking the path for any new EU migrants to come to the UK after the end of 2020, on top of the effect of many returning home during the pandemic, they have ensured that labour shortages can only get worse from here.

While there is nothing to stop the government loosening immigration rules, which are both cruel and counterproductive given the shortage of workers, it has instead so far doubled down on its “hostile environment” approach. EU citizens arriving in Britain have been detained and even expelled from the country. The government prefers posing as “tough” on migrants even while doing so does real economic damage.

One of the central myths that drove the Brexit vote is the idea that migration ‘takes’ something from Britain, including ‘taking our jobs’, costing money in benefits, causing pressures on public services, etc. With free movement now ended, we see the reality. Migrant workers were keeping entire sectors running – and they were propping up our public services too! There is no jobs bonanza for those who voted for Brexit in the hope of getting back ‘their’ work – skills and experience gaps mean it does not work that way – just labour shortages leading to food shortages and price increases.