Chapter 8: Britain’s place in the world

At the moment there are a thousand issues pushing Britain back towards alignment with the EU, and very little pulling in the opposite direction. One clear danger however is the enthusiasm of Boris Johnson’s government for trade deals.

The Tories appear willing to sign up to new trade deals on terrible terms, committing Britain to one-sided trading arrangements for decades to come. These deals serve two purposes for the government. Firstly, they make Brexit look like a success – the quality of the trade deals does not particularly matter to this government as long as it can boast about how many it has done. Secondly, any deal that is not a simple ‘carry over’ of the previous deal with the EU changes the legal framework for trade with that country, and so entrenches Brexit.

Paradoxically, the trade deals are not being agreed because Brexit enables better deals, but because doing the deals now makes Brexit more difficult to unravel later.

The infamous US-UK trade deal, which would have brought chlorinated chicken and hormone-fed beef to Britain and spread it quietly across our food chain, has been largely defeated with the end of Donald Trump’s presidency (see Conclusion). However, the broadly similar deal with Australia, which also includes meat imports with another range of bad animal welfare practices that are banned in the EU, has been ‘agreed in principle’, and will soon be published and move to its next stages.

According to the RSPCA, “Australia has lower legal animal welfare standards than in the UK, including barren battery cages for hens, chlorinated chicken, sow stalls, growth hormone treatment for beef and journey times of up to 48 hours without rest and live exports when the UK Government is looking to stop live exports and significantly reduce journey times.

“In addition, because production methods in Australia can be cheaper, flooding UK supermarkets with cheap, low welfare Australian imports would put UK farmers’ livelihoods at risk.”

The Australia deal also risks disrupting the Northern Ireland protocol, as food produced in Britain using Australian ingredients will not comply with EU rules.

To rejoin the EU, it is important to fight these toxic trade deals, and to be part of coalitions raising the problems with them and attempting to remove the worst sections.

Geopolitical realignment

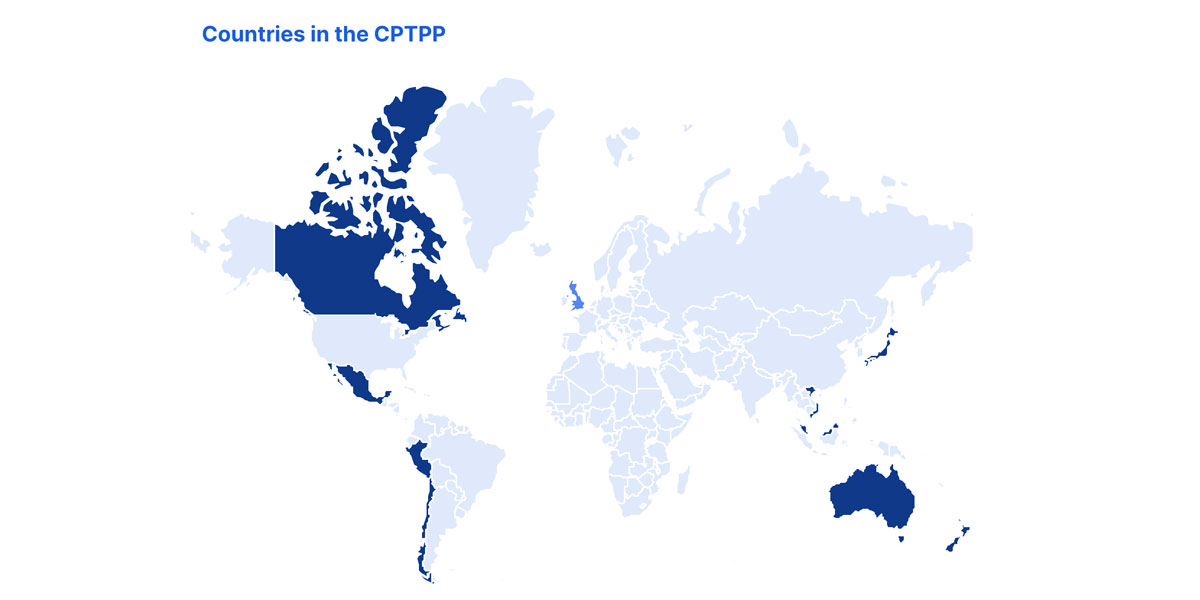

The Australian deal is a stepping stone to what the UK government considers the real prize: membership of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). The UK has launched accession negotiations to join CPTPP. The government says this is “pivoting Britain towards some of the world’s biggest economies of the present and future”.

For Britain to join CPTPP is absurd not least because it is a collection of countries on the other side of the world: Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, Japan, etc. All 11 members are on the Pacific Rim. The UK, as you may have noticed, is not. It means we would have left our local trade bloc to join one where all trade means transport over extremely long distances, with the corresponding implications for climate change. This is a triumph of “Britannia rules the waves” wishful thinking over reality – the same mindset that is seeing Boris Johnson spend £200 million on a new ship to promote “the UK’s burgeoning status as a great, independent maritime trading nation”. It is a government that has forgotten which side of the world it is on and which century it is living in.

It represents an attempt at a geopolitical realignment and threat to future EU membership as CPTPP membership comes with a whole alternative trade bloc rulebook: it is somewhat like the EU in that it enforces a set of common standards, but unlike the EU in that they are mostly completely different standards. Labour’s shadow international trade secretary Emily Thornberry sent a letter with 230 questions for the government about the practical implications of joining CPTPP. These include:

“As part of the accession process, will the UK have the right to negotiate exemptions from any provisions of the CPTPP agreement to which we do not wish to accede, and amendments to those provisions we wish to improve, or will joining the CPTPP mean accepting its current provisions in full?”

“If the government intends to accept the existing CPTPP provisions without modification, how will it square that decision with its commitment to the British people that – as a matter of principle – post-Brexit Britain must be a rule-maker and not a rule-taker?”

“In keeping with their manifesto promises, can the government guarantee that nothing in our accession to the CPTPP will lead to the increased sale of food in the UK produced to lower standards of food safety and animal welfare than are currently legal for farmers in Britain?”

“Will the government guarantee that Britain’s health and care services will be entirely exempt from any of the provisions of the CPTPP that will apply to the UK?”

… and many more. To date the questions have gone unanswered, but joining CPTPP continues as a central aim of UK trade policy.

This focus could be because CPTPP is also a possible Trojan horse for a trade deal with the US. While the US is not currently a member, it was previously part of the deal before Trump withdrew from it in 2017, and under Biden is thought to be minded to rejoin at some point. The Financial Times reported that Boris Johnson “hopes Joe Biden, US president, will join the group too, opening a backdoor to closer UK/US trade ties”.